Finally! After the original Resident Evil was recently made available for purchase on PS5, I wondered when, if ever, the entire 90’s trilogy would be unified, and also why it wasn’t already. As much as I hoped, there was no sign of Leon S Kennedy, Claire Redfield, or Jill Valentine’s pixelated selves on the PlayStation store, only their supermodel counterparts, aka the stars of the remakes. Was this an effort by Capcom to push the reimagined iterations of each title into canon? To pretend the classics were entirely outdated and absolutely needed to be recreated in the first place? That’s the kind of conspiracy Umbrella would cook up. . . Well, whatever the case, Resident Evil 2 and 3 have returned. I’m sure there are many people who noticed these same arrivals on the PS store with the indifference of Ada Wong, but I reacted the way Chief Irons would if the mayor’s daughter came back to life just so he could kill her again. . . okay, I might need to work on my analogies. . . I can’t relate to a felonious taxidermist murderer, guys, I promise. . . Let’s just say I was thrilled to play some of my favorite games once again. I was met with memories of being only 4 or 5 with a bowl of goldfish crackers by my side as I rocked back and forth in a hard, plastic children’s chair on the floor, unaware of how to proceed past the first few rooms of the RPD and utterly bewildered by the lack of skin on a Licker. Who the hell was letting me play this back then, anyway? Oh, well, I turned out alright, so long as we ignore that Chief Irons thing.

Loading up the original Resident Evil 2 felt somewhat strange. Here I was again, back to where my love for the franchise truly began as a mesmerized kid. However, I didn’t feel as though I was catching up with an old friend just yet. Though Leon and Claire’s tumultuous night of terror in Raccoon City has stuck with me through the years like a benevolent Mr. X, I realized while staring back at the iconic title screen that I haven’t played Resident Evil 2 in a disappointingly long time (due to its lacking accessibility). I used to own a digital port on the PlayStation 3, but that was lost after my account suffered a glitch from which it never recovered. The 2002 remake of Resident Evil is the installment I’ve played most often. That’s kind of ironic, as I don’t have as many core childhood memories of attempting to get through the original game as I do the second, yet I must have played through the glorious remake dozens of times on the GameCube, Wii, PS3, 4, and 5. To this day, I usually run through it at least once every Fall. Resident Evil 4 is probably my second most-completed RE game, followed by the Resident Evil 2 remake. Then it’s an approximate tie between Zero and Code Veronica, with the rest trailing somewhere behind. In other words, I didn’t know for sure how well the game was about to hold up, and that uncertainty made me slightly nervous, as there’s nothing sadder than watching nostalgia mutate into a nasty, pessimistic monster like it just entered the fourth stage of a G-virus infection.

When revisiting any type of art that sent lightning bolts blasting through our brains way back in the day, we must remember the context of its initial release. Contextual awareness fills the gaps between then and now, creating a bridge of understanding between aspects that haven’t aged very well, and others that still hold their own in the face of the future. For instance, during my Leon A playthrough, I was already becoming slightly impatient when completing the statue “puzzle” on the second floor of the police station, which requires players to slowly push statues across a small room for the sake of accessing a valuable red jewel. As I tried to align the statues at a weird, unchangeable camera angle, I was on the verge of giving in to a toxic frame of mind, brought on by years of instant gratification. However, contextual awareness swooped in to save Capcom’s survival horror masterpiece from unfair scrutiny, as I reminded myself that pushing statues over pressure plates to reveal a key item, manipulating the environment itself to progress further, was quite novel in 1998. Sure, it was already done in Resident Evil two years prior, and the concept most likely didn’t inspire anyone to point at the TV screen yelling, “I can push the statue! I can push the statue! but it’s an aspect of the game that falls under the “neat in the 90’s” category, thus validating its inclusion. If the rest of the game overcomes relic status for most of its runtime, then moments that don’t match “modern expectations” become little time capsules for us to appreciate.

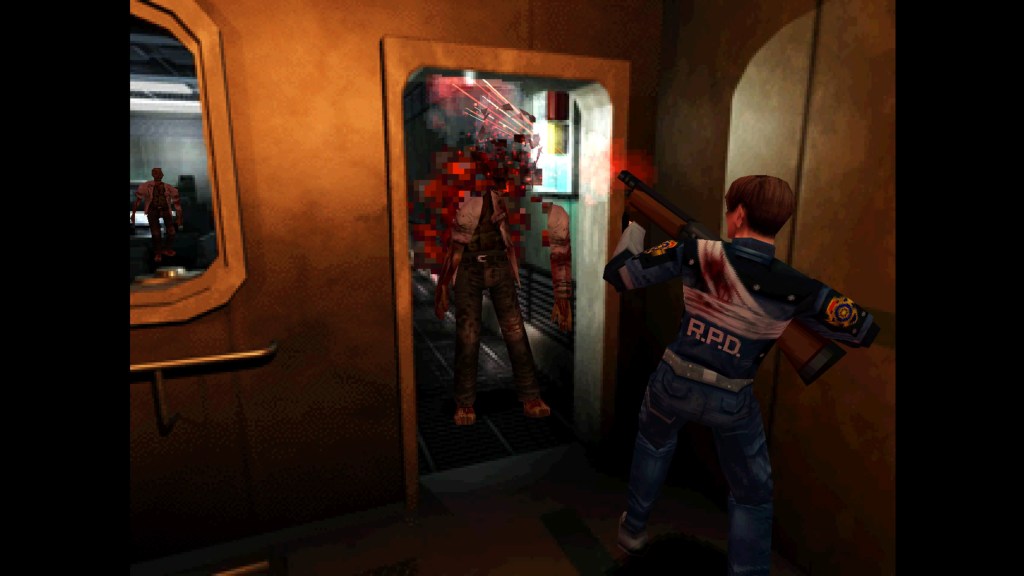

As I made my way through the RPD, I discovered that employing contextual awareness was a decreasingly necessary factor in genuinely enjoying the experience for what it was and still is. Obvious signs of age (graphics, controls, voice acting) rarely needed to be justified. Maybe because of all the fantastic contemporary indie games I’ve played (many of which bring retro graphics and sometimes retro controls back into the limelight), the old feels new again. Titles like Signalis and Dusk have reminded us that artistry triumphs over flashy technology, every single time. In 1998, Resident Evil 2 looked pretty great, and in 2025, I often stopped to admire the masterful mixture of pre-rendered images and live pixelation. Standing at the top of a steel staircase on the roof of the police station, Leon stares stoically ahead. Behind him, the striated night sky shows no sign of lifting as the carcass of a crashed helicopter roasts in bright orange flame below. It’s an incredible visual, like something out of dream. . . or a nightmare. . That these moments can have such a hold over my imagination almost 30 years later proves passionate craftsmanship is the gateway to longevity. It’s not just about the graphics, it’s how they’re used to serve themes and build atmosphere. The same goes for establishing an engaging storyline in a videogame. How the story is told determines whether it will be cherished or forgotten. Was the player directly involved in every event? Did the narrative intertwine gracefully with the gameplay, or was it unfolding in spite of it?

Many mainstream titles have become nearly indistinguishable from one another. As the obsession with realism continues, finer details fade away. It’s as if publishers and developers have ensnared themselves in a trap. The high price of games go hand in hand with braggadocios demonstrations of wind physics and beads of sweat trickling down a character’s face. However, after all that time and money is spent on showing off, gamers are left to ride around on a horse for hours on end, repeating the same monotonous tasks until a 50-hour runtime is achieved; another false merit of the asking price. On the other hand, short single-player campaigns stuffed full of the same tropes and stale “cinematic” conventions are presented alongside a basic multiplayer mode that hopefully distracts everybody enough to forget about the fact that a better version of this same thing already existed back in 2006. But what can be done? The new standard has been set.

Part of that new standard is a spike in hiring famous actors to portray gaming protagonists. You’d think this would also guarantee an incredibly stark difference between voice acting performances then and now. Not true. I’ve never factored voice acting very heavily into my overall rating of a game and I still don’t. Nothing has been done consistently enough to convince me that games have any business striving for Oscar-level gravitas. Videogames are, by nature, somewhat ridiculous. Gaps in logic or basic science, such as being capable of healing a bleeding gash by consuming an herb, or whacking a dragon’s ankle with a wooden club until it dies, preserve the fun. Just let games be weird and kind of stupid, we promise not to think too hard about it.

With that being said, Resident Evil acting has always been notoriously hammy, so much so that fans, including myself, adore it. But the acting in Resident Evil 2 isn’t that bad, especially for ’98. The performances are an improvement over the first, no doubt. I thought the somewhat awkward and stilted delivery typically aligned with the surrounding situation, as strangers tensely and suspiciously interacted with one another while trapped in a deadly maze. Maybe that’s a stretch, but there are many classic lines on display, such as when Leon smoothly tells Claire, “It’s good to see you’re still among the living” as the two reunite inside of the S.T.A.R.S. office, and I’ll never grow tired of his petulant, over-dramatic “Ada, wait!” whenever the undercover agent goes running off on her own (it happens a lot). Also, Ben the journalist goes out like an absolute G. “Get that scum,” he growls, referring to Chief Irons as the life drifts away from his torn-up body. “Make. Him. Pay.” Finally, listening to Chief Irons expose his own chilling delight at the opportunity to experiment on cadavers and act like an overall freak provides just as much entertainment as the screams he unleashes when he eventually meets his disgusting doom. The voice acting is another element of the game that betrays its age while simultaneously increasing its individualistic impact and sense of legacy. I’d rather remember lines for being appropriately cheesy than listen to static expository reads (Ada from the Re4 remake, I’m looking at you).

As I continued through Resident Evil 2, I settled back into that familiar flow of exploration, resource management, dangerous back-tracking, and risk-taking. It all felt so . . . fresh. I couldn’t allow myself to stop and save at a typewriter until I tied up one more loose end . . . then another one . . . and maybe one more, just because the Heart Key door is so close. It’s relevant to note that this port is really an emulator, meaning the creation and loading of a save file is accessible at any time via an extra menu, along with the ability to rewind the game to amend a mistake, though I did my best to avoid using such sacrilegious features. Yes, it’s true. I admit that I’m not perfect. I forgot to bring the valve with me at one point in the sewers and couldn’t bear the boring backtrack to the item box, so I rewound the game instead, cutting my trip in half. You could suggest this corrupts my organic revisitation of classic Resident Evil, and I’ll concede such a claim to some degree, but if the rewind option didn’t exist, it’s not as if I would have quit. Once, while playing as Claire, I barely scraped by in a battle against a G-Type Adult and was left hobbling out from the underground. I shuffled slowly toward the exit but was prevented from moving on. I had to limp all the way back to the previous room so I could escort Sherry. Nope. I have to make dinner soon, so let’s rewind that part real quick…

Aside from a bit of tedium tossed into the mix (which is arguably still a staple of survival horror to this day; a necessary evil perhaps) Resident Evil 2 didn’t contain anything that caused me to sit back and reflect on how far the gaming industry has come. If anything, I pondered the opposite. From the moment I entered the vaulted entrance hall of the RPD, I was excited to rediscover all the nooks and crannies embedded into this creepily curated building that once served as a museum. The hauntingly echoey musical track that dances lightly beneath an air of musty mystery lured me toward the wooden doors on either side of the hall, urging me to stumble upon strange artefacts and valuable resources in whichever way I saw fit. Questions I wish I was forced to ask myself more often were once again at the forefront of my mind. Do I clear this hall now or save my ammo and test my luck in the Licker hall? Should I stop at an item box before I enter the sewers, or depend on new discoveries to keep me alive? Do I use the cord to close the window shutters in the east wing or the west?

Easily distinguishable sections of the station give way to the swampy sewers and finally the lab, establishing a convincingly interconnected world coated in secrets and conspiracies that tantalize rather than smother. In other words, the lore is expanded upon just enough from the Spencer Mansion incident. The focus is still on one seemingly unremarkable Midwest town, where our unlucky protagonists never expected to fight for their lives against ravenous rotting civilians, clinically insane police chiefs, disgraced scientists, and whatever else lurks behind each door. The adventure is at once cozy and claustrophobic. It takes place on a relatively small scale with nods to an over-arching tale of terroristic experimentation, rather than completely pulling back the curtain to reveal a chaotic action movie about global threats, such as what Resident Evil 6 would go on to do years later. At the center of it all is a cautionary tale of perfectionism and obsession, leading to a conclusion soaked in darkness and tragic loss, despite Leon, Claire and Sherry’s ultimate survival. Story beats overlap between scenarios, as each protagonist experiences their own alternate offshoots to a shared path. The parallels aren’t perfect. Some of the same ground is retread (like pushing those damn statues), though the dedication to completing a cohesive vision via multiple playthroughs remains a rare idea, at least in the mainstream market.

When I decided to write about Resident Evil 2, I was initially tempted to compare it to the remake, though plenty of those direct comparisons already exist in great detail, and I would rather appreciate the original game on its own. The lifespan of Resident Evil 2 is never-ending, a reflection of the ambition and passion that went into its creation. Developers that copy and paste gameplay mechanics, UI, sequencing, transactional traps, and in-game excuses to extend runtime from one another, all while cropping intriguingly risky decisions for the sake of retaining higher player bases, results in a dour landscape where titles blend together and are lost in the shuffle. From the moment you press start, Resident Evil 2 stands out. So many signs of going the extra mile exist within its sights, sounds, and level of player input. Yes, the remake is a lot of fun to play, and I’m glad it exists, though it’s not something I would have ever clamored for with the real deal right in front of me. So, if you find yourself reaching for one of the Resident Evil remakes at the end of this spooky season, then let’s pretend your name is Ada for a second. . . ADA, WAIT! Play the classics instead. I promise you won’t be disappointed, so long as you’re not one of those people who can’t seem to ever make sense of tank controls (no shame). If that’s the case, then you’ll probably hate it.

Until next time, peace out!

Leave a comment